Introduction to the grand narrative of independence.

History, as written by the victors, often distorts the truth. While Simón Bolívar is celebrated as the “Liberator” of South America, the reality is far more complex. Behind the grand narrative of independence, there were men who fought not just against Spain but against racism, class oppression, and the betrayal of their own so-called allies. Yet, these true revolutionaries—many of African and Indigenous descent—were erased from history or deliberately vilified to ensure that power remained in the hands of the white Creole elite.

This article brings Manuel Piar and José Prudencio Padilla back into the center of the independence story. Both men led crucial battles, risked everything for true liberation, and were ultimately sacrificed by the very republic they fought to create. Their executions were not just about political maneuvering—they were calculated acts of racial and social suppression, ensuring that nonwhite leaders would never hold real power in the newly formed republics.

It is time to rewrite the Eurocentric history of Latin American independence and honor those who were silenced. By reclaiming the legacy of figures like Piar, Padilla, and the many forgotten Afro-Caribbean fighters, we begin to heal the psychological and historical wounds inflicted by a system that continues to marginalize their descendants.

The Invention of “Pardocracia” and Bolívar’s Fear of Racial Power Shifts

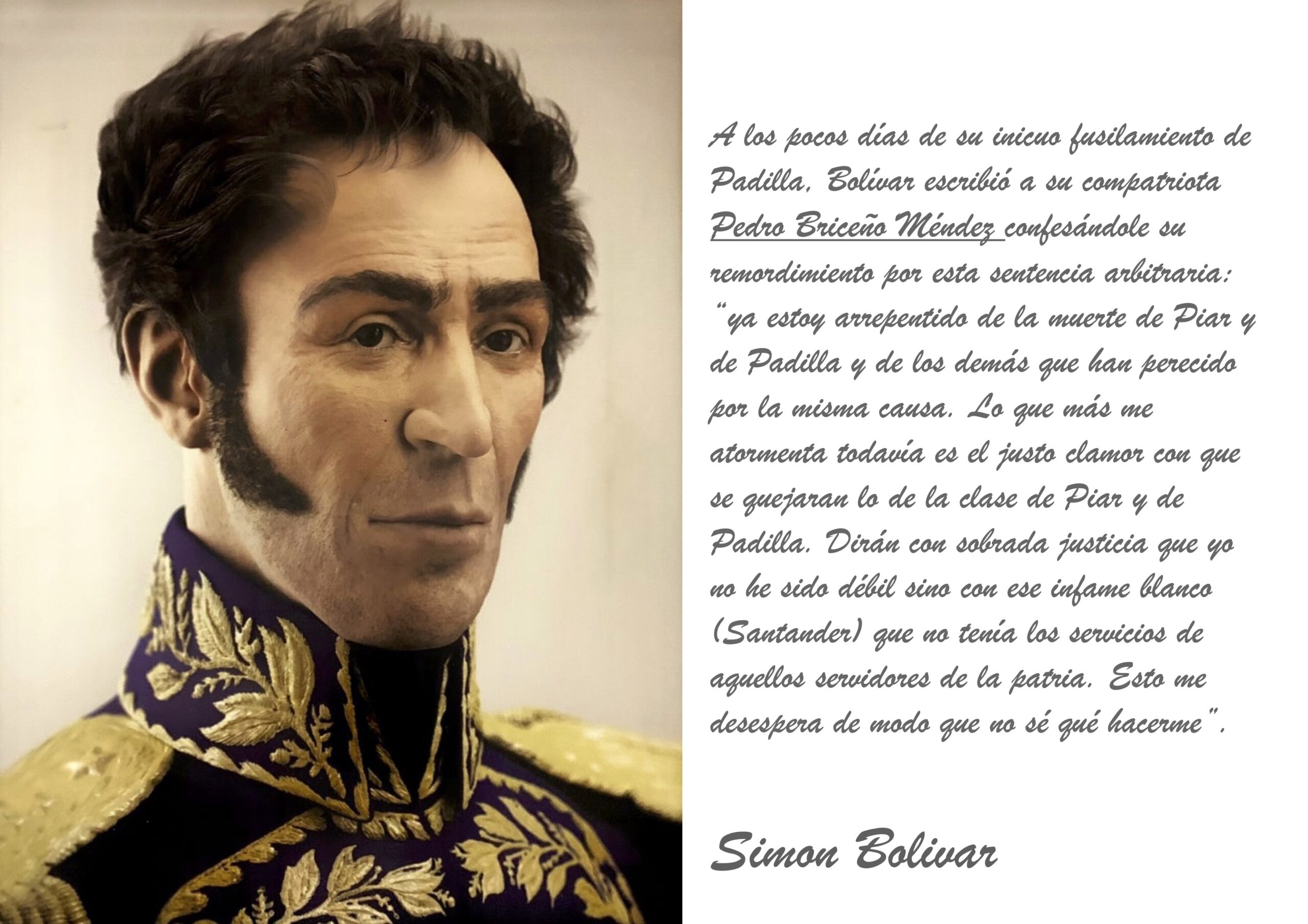

The term pardocracia—first used by Bolívar in his 1825 letter to Gran Colombia’s vice president—expressed his fear that legal equality would not be enough to pacify the pardo population. He warned that pardos, if given too much power, would not stop at equality but would exterminate the privileged white class.¹ This reveals Bolívar’s deep anxiety about social change: he wanted to control racial tensions, not eliminate them.

Simon Bolivar’s fears were rooted in the Caribbean revolutionary context, particularly the Haitian Revolution, where enslaved people and free people of color overthrew their white rulers and established an independent Black republic. Haiti had supported Bolívar’s independence movement under Alexandre Pétion, who demanded the abolition of slavery in return.² However, Bolívar ultimately distanced himself from Haiti’s radical example, choosing gradual emancipation over immediate abolition to avoid unsettling the white Creole elites.³

The Political Execution of Manuel Piar: A Warning to Nonwhite Leaders

The Political Execution of Manuel Piar: A Warning to Nonwhite Leaders

Bolívar’s paranoia over pardocracia played a crucial role in his decision to execute General Manuel Piar in 1817. Piar, a mixed-race leader of great military talent, had challenged Bolívar’s authority and called for a more radical social revolution that included racial equality and redistribution of power. Rather than allowing Piar to become a symbol of pardo autonomy, Bolívar had him executed on charges of conspiracy and insubordination.⁴

Yet Bolívar’s speech before Piar’s execution was revealing: he accused Piar of promoting a racial war that would divide the republic. This accusation was ironic, given that Bolívar himself had used racial rhetoric to rally Afro-descendant and Indigenous troops against Spain.⁵ The execution of Piar was a calculated move to reassure the white elite that Bolívar would not allow nonwhite leaders to claim real political power.⁶

José Prudencio Padilla and the Repeated Cycle of Suppression

José Prudencio Padilla and the Repeated Cycle of Suppression

A similar pattern emerged a decade later with José Prudencio Padilla, a celebrated Black naval officer who had secured crucial victories against Spain. Despite his service, Padilla was never given the full recognition or authority that his white counterparts enjoyed. Instead, he faced constant racial discrimination and political sidelining.⁷

In 1824, Padilla issued a bold proclamation in Cartagena, warning that he would not allow his class (the pardos) to be excluded from power. His words echoed Piar’s calls for racial justice: “The sword I wielded against the King of Spain, that same sword that has brought glory to our nation, will now defend my class and my dignity”.

Bolivar’s Reactions

Bolívar’s reaction to Padilla’s assertiveness was immediate. In 1828, following the so-called “September Conspiracy” against Bolívar’s rule, Padilla was accused of involvement. Although the actual plotters were mostly white Creole liberals, Padilla was singled out, imprisoned, and executed.⁹ His death sent a clear message: nonwhite leaders, no matter their contributions, would not be allowed to challenge Creole supremacy.¹⁰

A “Democratic” Republic for the Creole Elite

Despite Bolívar’s rhetoric about liberty and equality, his vision for Gran Colombia’s government was inherently exclusionary. His 1819 Constitution proposed a hereditary Senate, ensuring that political power would remain in the hands of the Creole elite.¹¹ His voting restrictions, which required literacy and property ownership, effectively disenfranchised the majority of nonwhite citizens, reinforcing a racial oligarchy.¹²

Even when Bolívar pushed for abolition, it was more a strategic tool than a genuine commitment to racial justice. In 1821, at the Congress of Cúcuta, he abandoned his earlier demands for total emancipation, settling instead for gradual abolition through free-womb laws.¹³ This gradualism ensured that slavery would persist for decades, keeping Afro-descendants in a subordinate position while preserving the Creole elite’s economic interests.¹⁴

Decolonizing the Historical Narrative: The Need for a New Perspective on Piar and Padilla

The execution of Manuel Piar and José Padilla is a stark reminder of how nonwhite heroes of independence were erased or vilified in Eurocentric historical narratives. Bolívar and his allies ensured that history was written in a way that preserved the myth of Creole supremacy and silenced the contributions of Afro-Caribbean and Indigenous leaders.

It is time to rewrite history from a decolonial perspective, centering figures like Manuel Piar, whose mother, Maria Isabel Gómez, left her island of Curaçao believing in the ideals of freedom only to see her son betrayed by the very movement he fought for. It is no coincidence that Afro-Caribbean leaders like Piar were eliminated while white Creoles consolidated their power in the new republics. The psychological scars of this historical betrayal of Afro-descendant communities continue to affect Latin American societies, where systemic racial inequality remains deeply ingrained.

To heal these wounds, we must reclaim the erased legacies of Piar, Padilla, and countless other nonwhite leaders who were sacrificed in Bolívar’s vision of an elite-controlled republic. By confronting these historical injustices, we can begin to restore the dignity of those who fought for true freedom—not just independence from Spain, but an end to racial oppression.

Tico Vos

Tico VosContent Creator

Tico Vos is a professional photographer, producer, and tourism specialist. He has been documenting the History, Culture, and News of Curaçao. This site is a documentation of the history of Manuel Carlos Piar.