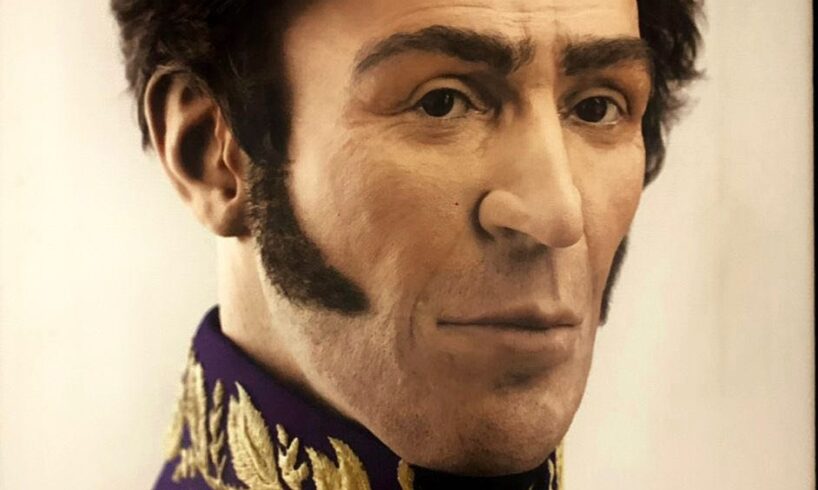

Bolívar’s Position on Slavery and Non-Whites in 1815

In 1815, Bolívar, exiled in Jamaica, wrote letters seeking British support for Spanish American independence. In these letters, he argued that a race war akin to the Haitian Revolution was unlikely in the Spanish American mainland. His reasoning was that white creoles, despite being a minority, possessed the intellectual qualities necessary for governance. He downplayed the presence of free blacks, mulattos, and zambos, focusing instead on the idea that enslaved people in Venezuela had been passive and loyal to their masters. Bolívar reassured his British audience that slavery did not pose a significant revolutionary threat.

In 1815, Bolívar, exiled in Jamaica, wrote letters seeking British support for Spanish American independence. In these letters, he argued that a race war akin to the Haitian Revolution was unlikely in the Spanish American mainland. His reasoning was that white creoles, despite being a minority, possessed the intellectual qualities necessary for governance. He downplayed the presence of free blacks, mulattos, and zambos, focusing instead on the idea that enslaved people in Venezuela had been passive and loyal to their masters. Bolívar reassured his British audience that slavery did not pose a significant revolutionary threat.The Execution of Manuel Piar

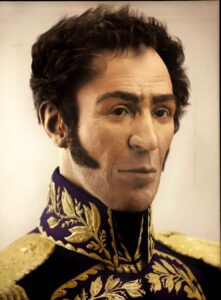

By 1817, Bolívar faced increasing challenges from military leaders of African descent, particularly Manuel Piar, a skilled general of mixed African and Spanish ancestry. Piar advocated for greater political and military inclusion of pardos (free people of African descent) and sought to establish a government more reflective of Venezuela’s racial and social composition. His growing popularity, particularly among the non-white population, alarmed Bolívar.

By 1817, Bolívar faced increasing challenges from military leaders of African descent, particularly Manuel Piar, a skilled general of mixed African and Spanish ancestry. Piar advocated for greater political and military inclusion of pardos (free people of African descent) and sought to establish a government more reflective of Venezuela’s racial and social composition. His growing popularity, particularly among the non-white population, alarmed Bolívar.Summary of the Document by Aline Helg:

Key points from the document:

Abstracts

Based on Bolívar’s speeches, decrees, and correspondence as well as on Gran Colombia’s constitutions and laws, this essay examines the tensions within Bolívar’s vision of Venezuela’s and New Granada’s society produced by his republican, yet authoritarian and hierarchical ideas, his concern for keeping the lower classes of African descent in check, and his denial of Indian agency. It shows that even in Peru, Bolívar’s main concern was to prevent the racial war and social disintegration that allegedly slaves and free Afro-descended people would bring to the newly independent nations. To prevent such an outcome, he advocated all along legal equality through the abolition of the colonial privileges and, since mid-1816, the abolition of slavery, but simultaneously the preservation of the monopole of power by the white creole elite. He secured the perpetuation of the socioracial hierarchy inherited from Spain by a two-edged citizenship: an active citizenship restricted to a tiny literate and skilled minority and an inactive citizenship for the immense majority of (mostly nonwhite) men. (Quote Aline Helg)

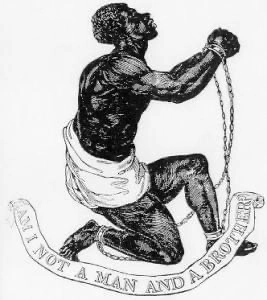

SLAVES AND FREEDOM

Regarding slaves, neither in 1815, nor in his previous correspondence did Bolívar advocate or even allude to their emancipation as a logical outcome of independence. He made no mention of the debates on slavery taking place then, or of the laws of gradual manumission adopted by most states in the U.S. North and by Antioquia, in New Granada (NASH & SODERLUND, 1991; MELISH, 1998; BLANCHARD, 2008, p. 34-35).

Alexandre Pétion

Bolívar began to promote the abolition of slavery only after his refuge in southern Haiti, where Alexandre Pétion, its mulatto president from 1807 to 1818, welcomed him from Jamaica, together with numerous refugees from Venezuela and New Granada. Pétion financed and equipped two successive expeditions that eventually allowed Bolívar and his followers to launch the final phase of their war against Spanish colonialism. In return, Pétion confidentially asked Bolívar to emancipate the slaves in the Spanish American territories he would liberate (idem, p. 189; O’LEARY, 1880, p. 343).

1819 The Congress of Angostura: Luis Brion not invited !

In 1819, with Spain losing ground in Venezuela, creole slaveholders regained strength and representation at the Congress of Angostura, which was elected to debate the creation of a joint Venezuelan and New Granadan “Republic of Colombia” (referred to here as Gran Colombia). Bolívar attempted to have the “proscripción de la esclavitud” written in the Fundamental Law of the new republic. Although most of his long speech to the congress aimed at convincing the delegates of the necessity of a British-inspired parliamentary system with a hereditary Senate (see below), it was also a desperate appeal in favor of the confirmation of his decrees emancipating the slaves, which, he claimed, had transformed them into enthusiastic supporters of the new republic. Brandishing the scarecrow of the Helotes, Spartacus, and Haiti, he stated: “[…] vosotros sabéis que no se puede ser Libre, y Esclavo a la vez, sino violando a la vez las Leyes naturales, las Leyes políticas, y las Leyes civiles. Yo abandono a vuestra soberana decisión la reforma o la revocación de todos mis Estatutos y Decretos; pero yo imploro la confirmación de la Libertad absoluta de los Esclavos, como imploraría mi vida, y la vida de la

República” (idem, p. 1141, 1152). Nevertheless, although the Congress of Angostura elected Bolívar as the president of the republic, the Fundamental Law it adopted did not mention abolition and ignored Bolívar’s emancipating edicts (as well as his parliamentary proposals) (URIBE, 1977, p. 699-702).

The failure by the 1819 Fundamental Law to declare the abolition of slavery, added to the death of President Pétion in 1818, probably weakened Bolívar’s commitment to the absolute freedom of the slaves.

A complex situation ?

Simón Bolívar’s legacy in relation to slavery and race is complex. While he took decisive steps toward abolition, these actions were pragmatic rather than ideological.

His fear of racial and social upheaval led him to suppress leaders like Piar, whose vision of a more inclusive revolution threatened Bolívar’s hierarchical model of governance.

Bolívar’s republic was designed to balance legal equality with the maintenance of a white creole-controlled political order.

This tension between republican ideals and racialized social control defined much of his leadership and left a lasting impact on post-independence Latin America.

Wikipedia on Aline Helg

Aline Helg is a historian, specializing in the history of slavery. She is known for her research and books on the history of revolutions, the Americas, the African diaspora, civil rights, racism and ethnicity.[1]

Biography

At the age of six, Helg and her parents left Switzerland to live in the United States. There, she experienced life in a country with a language unknown to her.[2]

She returned to Switzerland to obtain her doctorate at the University of Geneva in 1983 and became a professor in the same institution in 2003.[3] As Switzerland offered her few opportunities as a historian after her doctorate, she began her academic career in America working on Cuba, and Colombia. She was interested in emancipation movements and the racial question, and focused on how people demonstrated resilience to build a dignified life.[4]

She subsequently taught at the Department of Political Science at University of Los Andes in Bogotá. She also taught at the Faculty of Psychology and Education sciences and at the University Institute of Development Studies of the University of Geneva and at the History Department of the University of Texas at Austin from 1989 to 2003.

History of slavery and revolutions

Aline Helg claims that the slave populations of the Americas did not wait for their freedom to be granted, rather they built autonomousemancipation strategies.[6]

Helg studied slaves in South America who obtained their freedom even before of the abolition of slavery occurred.[7] In her writing, she examines the means by which the enslaved became free[8] and found that active rebellion was not the most effective nor the most common form of emancipation. Browning (the flight towards the still unexplored American territories), emancipation through military conscription, the manumission participation, and integration of the slave point of view in the discourse on freedom are constitutive strategies developed gradually and a discreet resistance leading little by little towards the resumption of their freedoms in a process called “encapacitation”. This research questions a vision of the 1980s that insists on impressive revolts and which somehow coincide with a sort of Santo Domingo syndrome.[9][10]

Aline Helg also wrote articles for different publications such as “Black Men, Racial Stereotyping, and Violence in the U.S. South and Cuba at the Turn of the Century,” published online by Comparative Studies in Society and History.[11]

Her book, Plus jamais esclave (Slave No More), tells the story of Francisque Fabulé in particular.[12]

Aline Helg regularly appears in the media as a specialist in the contemporary history of South America.[13]

Book chapters

-

Race in Argentina and Cuba, 1880 1930, Edited by Richard Graham, Published July 2010.[14]

-

Race in Post-Abolition Afro-Latin America, with Kim Butler, pages 257 to 288

Awards

In 2016 she received the award of the “Académie romande” for her work Plus jamais esclave.[15] The book explores the liberation strategies adopted by the victims of slavery themselves in the Americas between 1492 and 1838.

References

-

ALINE HELGCURRICULUM VITAE

-

Dom Tom (2018-01-05). “Aline Helg pour memorado.ch”. YouTube. Retrieved 2018-10-03.

-

Aline Helg

-

Prof. Aline HELG

-

“Aline Helg – Biographie, publications (livres, articles)”. www.editions-harmattan.fr (in French). Retrieved 2018-10-03.

-

AfroCubaWeb

-

Las Independencias Hispanoamerica

-

La-Croix.com (2016-05-12). “Esclaves et insoumis”. La Croix(in French). Retrieved 2018-10-03..

-

Le syndrome de Saint-Domingue. Perceptions et représentations de la Révolution haïtienne dans le Monde atlantique, 1790-1886

-

Comme chaque vendredi ce matin nous laissons la place à l’actualité en histoire

-

Black Men, Racial Stereotyping, and Violence in the U.S. South and Cuba at the Turn of the Century

-

Plus jamais esclaves ! (French Edition)

-

“Géopolitis : – Magazine – Télé-Loisirs” (in French). Retrieved 2018-10-03..

-

The Idea of Race in Latin America, 1870-1940

-

Une historienne genevoise autopsie l’esclavage aux Amériques

Tico Vos is a professional photographer, producer, and tourism specialist. He has been documenting the History, Culture, and News of Curaçao. This site is a documentation of the history of Manuel Carlos Piar.