“A Black Man with a White Mask”: The Racial Betrayal of Manuel Piar

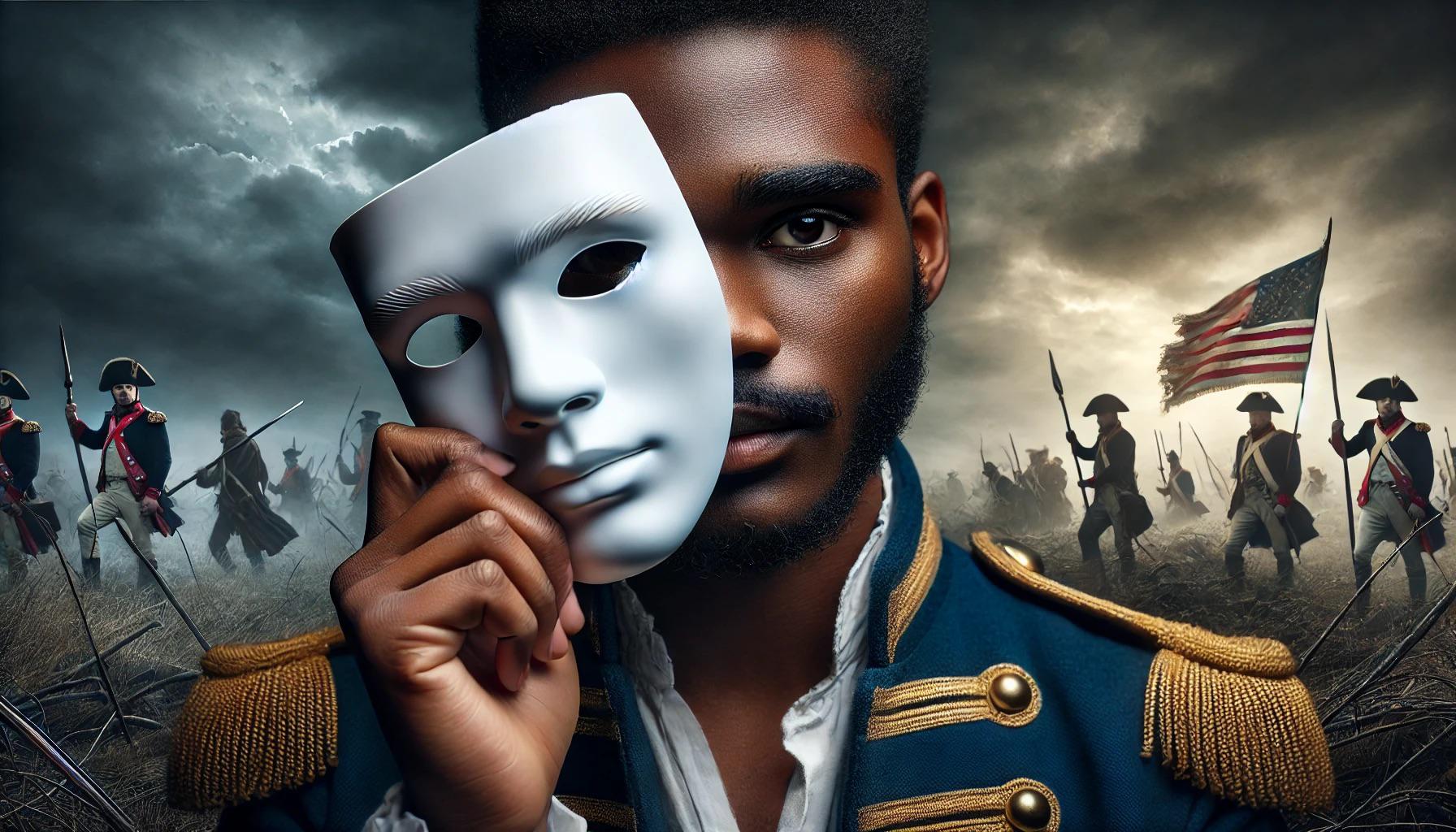

Manuel Piar, one of the most brilliant military strategists of Venezuela’s independence movement, was openly nicknamed with contempt—the Mantuanos and even some of his supposed allies called him “Negro con máscara blanca”, a Black man with a white mask.

It was a deliberate act of erasure.

Despite his blue eyes, red hair, and European features, the Venezuelan elite refused to see him as anything but Black. Not because they truly saw him as African, but because they wanted to deny him any claim to power, leadership, or equality. His features were ignored; his military genius was reduced to mere instinct; his victories were seen as an accident rather than the product of skill and strategy.

This labeling was strategic—it was designed to remind him (and everyone else) of his place in the racial hierarchy. No matter how much he accomplished, no matter how much he outperformed Bolívar himself, he would never be allowed to fully belong to the ranks of the Criollo elite.

And that, more than anything, sealed his fate.

The “Mask” They Forced Upon Him

Piar did not see himself as a racial revolutionary, but he became one by default—because the system gave him no other option.

He was a man of all peoples—born in Curaçao, raised in a world where he faced no discrimination, fluent in Papiamentu, Dutch, Spanish, English, French, and Guene, and later learning three Indigenous languages. He connected with all social classes, commanding armies of freedmen, Indigenous warriors, and even Criollo officers.

He was not wearing a mask. He was not pretending to be something he was not.

Yet, the white Criollo elites insisted on seeing him only as Black. They stripped him of his European heritage, his multilingualism, his strategic brilliance, and reduced him to a single racial category—one that disqualified him from power.

They could not accept that a man of mixed race could be superior to them in battle, in leadership, and in vision.

And Bolívar—who was both Piar’s ally and, ultimately, his greatest adversary—felt that contradiction deeply.

Bolívar’s Fear: The Man Who Dismantled His Worldview

Was Simón Bolívar truly the champion of racial equality he claimed to be? Or was he just another Criollo who saw non-whites as useful tools rather than as equals?

In his writings, Bolívar openly expressed deeply racist views:

“Los indígenas y los pardos son incapaces de gobernarse por sí mismos; sólo los blancos tienen la civilización necesaria para llevar las riendas del Estado.”

(“The Indigenous and the mixed-race people are incapable of governing themselves; only whites have the civilization necessary to lead the State.”)

But Piar’s very existence was a direct contradiction to this belief.

•• How could Bolívar claim that only whites were fit to rule when Piar, a man of mixed heritage, was the most victorious general in the entire independence movement?

•• How could Bolívar justify the racial hierarchy when the soldiers who fought hardest for independence were the very people he believed could not govern themselves?

•• Piar was not just a threat to Bolívar’s military position—he was a threat to the entire racial and social order that Bolívar still, consciously or unconsciously, upheld.

•• This is why Piar had to be labeled and discredited.

•• He had to be reduced to a racial stereotype—“Negro con máscara blanca.”

•• He had to be stripped of his victories, his strategic mind, and his leadership.

•• And ultimately, he had to be eliminated.

The Execution of a Revolution

In 1817, Bolívar, pressured by the Mantuanos and afraid of Piar’s growing influence, ordered his arrest. The charge? Conspiracy and insubordination.

The real reason? He was too victorious, too independent, too much of a leader.

Despite no solid evidence of treason, Piar was sentenced to death and executed by firing squad on October 16, 1817.

His crime was not betrayal.

His crime was being too powerful, too successful, and too non-white to be allowed to exist in the new Venezuela.

The Hypocrisy of the Criollo Revolution

— Piar’s execution was not just a military betrayal—it was a racial and political statement.

— The Criollo elite, who spoke endlessly about liberty, justice, and equality, showed their true colors when faced with a leader who did not fit their racial mold.

— They fought for independence from Spain—but only so they could replace Spanish power with their own.

— They called for freedom—but hesitated to free the enslaved.

— They spoke of justice—but executed the very man who won them their victories.

Piar was not a Black man with a white mask—he was a leader whose legacy exposed the masks of others.

He exposed Bolívar’s own contradictions.

He exposed the Mantuanos’ fear of racial equality.

And he exposed the unfinished revolution that continues to shape Latin America today.

A Legacy That Cannot Be Erased

Piar’s story is a reminder that history is not written by the most just, but by those in power.

•• His name was nearly erased.

•• His victories were downplayed.

•• His image was reshaped to fit the Criollo narrative.

But the people who fought alongside him never forgot the truth.

•• The Indigenous, the Black, the forgotten soldiers of the revolution remembered the real Liberator of Guayana.

•• And today, his story continues to challenge the myth of Bolívar’s revolution—a revolution that promised freedom but still feared true equality.

Piar’s death was meant to silence him.

•• Instead, it became proof of the unfinished fight for justice, for recognition, and for a revolution that includes everyone.

The Execution: A Political and Racial Betrayal

In 1817, Bolívar, pressured by the Mantuanos and afraid of Piar’s growing influence, ordered his arrest. The charge? Conspiracy and insubordination.

The real reason? He was too victorious, too independent, too much of a leader.

Despite no solid evidence of treason, Piar was sentenced to death and executed by firing squad on October 16, 1817.

His crime was not betrayal.

•• His crime was being too powerful, too successful, and too non-white to be allowed to exist in the new Venezuela.

The Hypocrisy of the Criollo Revolution

•• Piar’s execution was not just a military betrayal—it was a racial and political statement.

•• The Criollo elite, who spoke endlessly about liberty, justice, and equality, showed their true colors when faced with a leader who did not fit their racial mold.

•• They fought for independence from Spain—but only so they could replace Spanish power with their own.

•• They called for freedom—but hesitated to free the enslaved.

•• They spoke of justice—but executed the very man who won them their victories.

•• Piar was not a Black man with a white mask—he was a leader whose legacy exposed the masks of others.

•• He exposed Bolívar’s own contradictions.

•• He exposed the Mantuanos’ fear of racial equality.

•• And he exposed the unfinished revolution that continues to shape Latin America today.

A Legacy That Cannot Be Erased

Piar’s story is a reminder that history is not written by the most just, but by those in power.

•• His name was nearly erased.

•• His victories were downplayed.

•• His image was reshaped to fit the Criollo narrative.

•• But the people who fought alongside him never forgot the truth.

From 1817 to 2022, efforts to clear his name continued. His reputation was rehabilitated, not because he was a martyr, but because the Venezuelan people recognized his contributions. They saw through the political execution and understood that he was not just a general—he was a liberator who never betrayed his people.

The Indigenous, the Black, the forgotten soldiers of the revolution remembered the real Liberator of Guayana.

And today, his story continues to challenge the myth of Bolívar’s revolution—a revolution that promised freedom but still feared true equality.

Piar’s death was meant to silence him.

Instead, it became proof of the unfinished fight for justice, for recognition, and for a revolution that includes everyone.

Legacy: The Face Behind the Mask

Legacy: The Face Behind the Mask

But his victories, his principles, and the loyalty of his people proved that he never needed a mask at all.

The revolution he envisioned —

A Venezuela where race did not determine power—is still a dream yet to be fully realized.

Tico Vos is a professional photographer, producer, and tourism specialist. He has been documenting the History, Culture, and News of Curaçao. This site is a documentation of the history of Manuel Carlos Piar.